SAM ADVANCED MANAGEMENT JOURNAL

Risk And Challenge Of Telemedicine Implementation During A Pandemic

Ghazala Yasmeen, Shafiq Rahman, and James Gelatt

DOI:

Citation: Yasmeen, G., Rahman, S., & Gelatt, J.(2021). Risk and challenge of telemedicine implementation during a pandemic. SAM Advanced Management Journal, 86(4),46-57.

Abstract

Telemedicine is an Information Technology (IT) system that supports medicine remotely for best patient care. COVID-19 has some crucial social, cultural, and economic impacts. It is directly affecting healthcare providers. Information Technology services are challenged to fulfill healthcare staff and patient needs. Its demand is expected to increase in the coming years.

The purpose of this paper is to explore the importance of organizational readiness and staff training to implement telemedicine and overcome technological challenges after COVID19. This paper will highlight the impact, risks, and values telemedicine can bring to our lives. Three themes originated in this systematic review (SR). They were the importance of telemedicine, technological challenges with telemedicine, and organizational readiness to implement telemedicine. The current paper is filling the gap to bring all three themes together for effective implementation of telemedicine.

The key findings emerging from this review indicate that telemedicine is a need of the hour, helping providers to meet the healthcare needs of patients by keeping social distancing. Organizational readiness and staff training play an important role to overcome technological challenges to effectively implement telemedicine. It is recommended that healthcare providers can effectively implement telemedicine and overcome the technological challenges depending on how much they are prepared as an organization to accept and learn this cultural change. Healthcare management and administration can play a vital role to identify the need and develop policies and procedures that support organizational learning and effective implementation of telemedicine.

Article

Introduction

The concept of telemedicine originated in United States during the 1960s by the National Aeronautical and Space Association (NASA) for monitoring of astronauts’ health in space (Link, 1965). After the success of this telemedicine approach by NASA, telemedicine is now widely used in the United States for medically isolated, rural, and suburban areas (Li, 1999) but has been urgently adopted as a safer technique for providing care during the novel coronavirus (COVID-19).

During COVID-19/Pandemic telemedicine is a quickly evolving practice by healthcare professionals to reduce the spread of infectious disease transmission (Whitney et al., 2020). Due to COVID-19 Pandemic, healthcare access in a safe setting became a priority as States are following CDC guideline and promoting social distancing.

COVID-19 is the first respiratory Pandemic since the 1918 Influenza. It, has severe social and economic impacts in general and especially on the healthcare system (Eftekhar et al., 2020). The current Public Health Emergency (PHE) due to COVID-19 has changed the conventional face-to-face services to the provision of telemedicine (Pollock et al., 2020). The telemedicine technology concept is not new but it is not yet widespread nor adopted by healthcare organizations before COVID-19/Pandemic. Currently, hospital systems are more vulnerable and exposed to security risks. Telemedicine is providing secured and accessible options to patients with healthcare needs and technology support. The CDC (Center for Disease Control) provided multiple guidelines in recent pandemic COVID19. This paper will also briefly highlight the role of healthcare providers, state administration, and IT to accommodate CDC guidelines.

The American Medical Association (AMA, 2020) highlighted that during COVID-19 Pandemic it is very important to keep physicians, healthcare workers, and patients safe. Therefore, telemedicine can help to support social distancing and continue to provide care virtually (AMA, 2020).In general, telehealth increases patient health outcomes and better results with patient care by avoiding a lot of scheduling conflicts.

The purpose of the current Systematic Review (SR) is to examine the literature about the role of organizational readiness and staff training for effective implementation of telemedicine during the pandemic. Although research on telemedicine is ongoing this current SR examines the findings from previous research to analyze the importance of organizational readiness to implement telemedicine. The current systematic review was conducted to further investigate the research question regarding the impacts, risks, and challenges of Information Technology (IT) services to fulfill healthcare staff and patient needs through telemedicine during a pandemic. The SR also looks at how organizational readiness and staff training can help to implement telemedicine during the pandemic. To answer these questions effectively, themes were identified across a body of literature reviewed. The three themes chosen for this systematic review (SR) were about the importance of telemedicine, technological challenges with telemedicine, and organizational readiness and training to implement telemedicine. The current study is filling the gap in research to bring these themes together to effectively implement telemedicine.

Technology brings a lot of changes to every business. If some of the healthcare organizations are not on the edge of technology available for telemedicine, they will fall behind. One of the greatest forces of change in the twenty-first century is the impact of information technology, which affects communication, entertainment, personal finances, and the ability to know about the world around us (Kreidler, 2019). Information technology provides a way to solve problems with business rules and needs. With the availability of the information source management and third party payment that specialize in these services, it becomes very easy to adopt technology in any organization. In healthcare, the adoption of technology is not in increasing demand, as compared to the other types of organizations, to solve their problems in business and to provide an advantage in the marketplace.

The healthcare industry standards are intended to protect patient privacy and hence must comply with many privacy and security laws, rules and regulations. The Health Information Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) imposes costly penalties on healthcare organizations for non-compliance with its privacy and security rules (Harvey & Harvey, 2014). Moreover, HIPAA requires healthcare providers to sign a business associate agreement with every data-sharing partner. As a result potential information technology vendors at times hesitate to come forward and implement technological changes.

The change in culture of using telemedicine from traditional ways of practicing medicine seems not an easy option for healthcare professionals. This change requires a lot of education, research, and willingness to change. Levingston (2013) mentioned that if telemedicine has been adopted e.g. for diabetic patient’s care, this could result in a 5.3 percent reduction in hospitalization and savings of $158,478 for every 1,000 patients. Hence, telemedicine saves cost, time, and lives of the patients where they can live a better, healthy, and long life.

Telehealth can be used for multiple modalities/types of care by the healthcare provider. A patient can talk to a healthcare provider or a doctor live either on phone or video chat. There are multiple platforms in the technology available to serve this need for telehealth. There are cloud-based services available for providers where they can communicate with patients through video calls. During live calls, patients can discuss their healthcare-related needs through voice or video and can see their results while providers are looking at the same time. This provides increased collaboration between both the parties to satisfy their needs by seeing actual results that the provider is viewing with them in real-time. At the same time, these applications have secured and encrypted interfaces with Electronic Medical Record (EMR) applications. There is a third-party component that addresses live chat as well. The interfacing between EMR application and telehealth tools serves the role of a bridge between both items. In some cases, providers have to log in to multiple platforms/applications to stay on top of the communication needs.

Technology is playing a vital role in the needs of patients and healthcare professionals. We know about the apple watch series 5 that has the capabilities to share high and low heart rates, menstrual cycles, ECG, fall risk, detect falls and call for help, sleep tracking, and a few other health-related items with their health care providers.

Providers can look at these results and can rely on the tests better without a patient visiting their office even for vitals etc. These technological tools provide flexibility on the part of the patient where they can provide initial vitals to physicians.

Edmunds et al., (2017) discussed that telehealth is a fast-growing sector that uses a wide variety of technologies to exchange information across locations and improve access, quality, and outcomes across the continuum of care. Thousands of studies and hundreds of systematic reviews have been done, but their variability leaves many questions about effectiveness, implementation priorities, and return on investment.

The next sections will explain the methodology, analysis, and synthesis along with some recommendations based on the above-mentioned themes. The paper will be conclude the SR with the emergent themes. This process was accomplished distinctly through the combination of numerous investigations and information collections to address a range of topics and prominent ramifications.

Identification of Evidence Search Terms/Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

After careful review of the importance and need for telemedicine and IT challenges to implement telemedicine, a specific research question was formulated for further study. The PICO model is used to develop research questions. PICO model helps to develop a precise, answerable research question that serves as the framework of the systematic review University of Maryland global campus (UMGC 1, n.d). The elements of the PICO framework were applied as follows:

P (Population): Healthcare providers and IT services.

I (Intervention): Telemedicine, organizational readiness

C (Comparison): Traditional healthcare arrangements

O (Outcome): Effective implementation of telemedicine

The following research question was developed with the help of the PICO framework.

What are the impacts, risks, and challenges of Information Technology (IT) services to fulfill healthcare staff and patient needs through telemedicine during pandemic?

Search String

The search string for the current Systematic review (SR) used (“telemedicine*” OR “telehealth *” OR “telemedical*”) AND (“implementation *” OR “apply*” OR “execute*”) AND (“Pandemic*” OR “Crisis*” OR “COVID 19*”). The original search string generated 304 articles. The number 304 is very broad so it was refined further by using the advanced search options and checked Boolean phrase to scholarly peer-reviewed journals only. In the next step, the search was further refined to select articles from 2016 to 2020. These filters narrowed down the number to 110 articles. Ultimately, 10 articles were fully reviewed for their rigor and transparency (Appendix A-B-C).

Analysis and Synthesis

Selected articles were analyzed for their rigor and transparency. Rigor is the practice of maintaining strict consistency with certain predefined parameters. From an academic perspective, Rigor is “applying the scientific method in the strictest sense to ensure an unbiased experimental design, analysis, interpretation and reporting results” (Prager & chambers et al, 2019, P.2). However, transparency, as used in science, engineering, business, the humanities, and in other social contexts, is operating in such a way that it is easy for others to see what actions are performed. Transparency implies openness, communication, and accountability.

The importance of transparency and rigor in a systematic review is to ensure the generalizability, credibility, and dependability of findings. It also provides practitioners with the best available findings depending on the specific question addressed in the review. There is no basic one-size-fits-all equation to analyze and synthesize the quality of research articles in any given range or topic, in general. Any topic may provide a wide variety of research studies using different research methods and tools, each centering on a distinctive perspective of the issue (Gough et al., 2012).

One common set of criteria utilized to evaluate research studies is TAPUPAS (Pawson et al., 2004). TAPUPAS stands for a group of characteristics i.e. Transparency, Accuracy, Purposivity, Utility, Propriety, Accessibility, and Specificity. Articles in this paper were analyzed by using this TAPUPAS framework (Appendix B).

The synthesize process had two parts — coding and grouping the codes. The approach used in synthesizing the articles was thematic synthesis. This approach was found to be more appropriate for this SR because the main purpose was to understand, analyze and synthesize the articles based on the findings. In other words, “the purpose of qualitative synthesis is to achieve greater understanding and attain a level of conceptual or theoretical development in any individual empirical study” (UMGC1, n.d.). In the coding process, both the inductive and deductive approach was used to create codes for the data. The reason for this is blending the two approaches provides flexibility in including the codes that are probably already known from the topic or from the hypothesis of the article as well as the emerging codes while reading the articles (UMGC2, n.d.).

ATLAS.ti was utilized as a method for coding. First, each of the articles was coded using the first cycle coding (UMGC3, n.d.). While coding the articles, definitions of all codes have been included as recommended by ATLAS.ti. Codes were grouped using ATLAS.ti. The common themes identified in selected studies were about the importance of telemedicine, benefits of telemedicine, technological challenges to implement telemedicine, organizational readiness to implement telemedicine.

Findings

There are three key themes originated from the current systematic review, i.e. importance of telemedicine, technological challenges with telemedicine, and organizational readiness and training to implement telemedicine.

Importance of Telemedicine

During COVID-19 a lot of organizations practiced telemedicine when their emergency and primary care departments were not open to the patients but only for COVID patients. After this pandemic, the shift may be changing and healthcare organizations and patients may accept the need for telemedicine. Growing evidence supports the use of telehealth from both the patient and caregivers’ perspectives (AMA, 2020). However methodological concerns of the current evidence may guide the direction of future research. System experience resulted in 81% satisfaction rating by the users of healthcare technology (AMA, 2020). The technology resulted in time and cost savings for patients, patient’s comfort, technical support, and operations and usability of telehealth technology was very satisfying for the patients.

Yvette DeVay (2020), explained that telehealth services allow beneficiaries to receive services from healthcare providers at their location. The communication between both can be synchronous. This two-way synchronous communication requires interactive audio and video telecommunication systems. It is a real-time conversation although both healthcare providers and healthcare receivers are apart.

Telehealth visits are safe and provide access to healthcare needs. This enables those who are vulnerable to COVID-19 to get basic health needs. Telehealth visits protected patient privacy and personal health information. Health and Human Service (HHS) made it easy for providers to provide telehealth service through commonly used technology while still maintaining guard rails to ensure privacy and personal health and protected health information.

Technological Challenges

Telemedicine is distance patient care; with the help of technology patients can get their healthcare needs at a distance supported by technology. In the current era, technology is accessible almost everywhere and provides an advantage in all areas of the world. Most businesses are adopting change brought by the technology and if any organization do not respond to this change, they will fall behind (Angela et al., 2020). Technology supports through multiple ways in the healthcare industry.

Technology provides all the tools required to serve patient healthcare needs especially clinical decision support systems. These systems in telemedicine consist of databases, patient portals, different EMR systems, video conferencing and data analytics, etc (Parks et al., 2019). Interfacing these clinical systems/telemedicine technologies is a little challenging.

Electronic medical record (EMR) especially Epic is used in more than 250 healthcare organizations in US, and 45% of the population has at least some of their medical records in Epic system (Day, 2020). Consumer technology is advancing rapidly where users have access to multiple advanced technologies in their hands all the time. These technologies can provide a lot of health-related items that were only available in hospitals before e.g. apple watch. This kind of technology can provide multiple life-saving tests and health-related data that can help caregivers to devise a health care plan for the patients. Mobile phones, tablets, and other devices like this are also available to the customers where they can communicate with anyone in the world (Smith et al., 2020). This also provides them with the ability to interact more with caregivers remotely and in real-time situations.

Video conferencing equipment and technology is not as expensive as it was in old times (a decade ago). A teleconferencing system cost about a decade ago was hundreds of thousands of dollars. Now we have video conferencing solutions in our hands due to advancements in technology. Corporate video conferencing systems are also very low in cost and readily available through cloud services where we can get these services as per corporate’s use. These cloud platforms are secured, accessible, cost-effective, and reliable to serve video conferencing needs.

Some studies explain that significant cost reduction has been recorded when telemedicine is used effectively. These save costs for the patients and the healthcare providers in terms of office space, office equipment, healthcare equipment, staff time, and travel, etc.

Organizational Readiness and Training

The first step to implement telemedicine is to identify options instead of conventional medical practice. Hospitals around the globe and in the United States are facing a real loss of outpatient care and hospital admissions. Due to the Pandemic, emergency lockdowns, and Center for disease control (CDC) guidelines, hospitals are not allowing patient visits unless it is a life-threatening emergency. In such situations, telemedicine is the best solution. Telemedicine can be used to build a bridge between patients and providers. Hospital administration needs to prioritize resources to meet their needs.

The next step is to build the team, identify the right people for the right job. Hospital management and administration must know who needs to be involved and when. Management needs to make sure the selected team has not only all the equipment and resources but they are also well trained. However, appointing new members and the whole IT set up is not an easy process. Many of the providers do not have their hospital or clinical IT, and prefer to hire IT services from a third party or vendor. Technology team members must be aware of the telemedicine laws and HIPPA compliance. HIPPA requires a business associate agreement with the technology provider (Smith eat al., 2020). If these associates were not already part of the hospital setup they then must understand the clinical needs and workflow. The technology team must be able to meet the challenges discussed in the previous section.

Hospital management must spend resources to train the team to do some basic troubleshooting. Physicians and nurses should be trained to make video onboarding smooth for patients. Since they cannot train the clients/patients — especially the elderly, providers need to set up simple guidelines. That starts by helping clients to checking through their junk mails for the invite to set up audio and video settings. Different providers have different workflows according to their needs and patient care. Generally, it starts with scheduling, either walk-in or appointments. Providers will set up virtual waiting rooms followed by online check in. Ideal telemedicine systems should have a full EMR (Electronic medical records) with scheduling, billing, notes, e-prescriptions, and search. Hospital systems are equipped enough to integrate different data sources i-e. Blood pressure cuff, Fitbit, smartphones app, Apple watch, etc.

Theoretical Framework

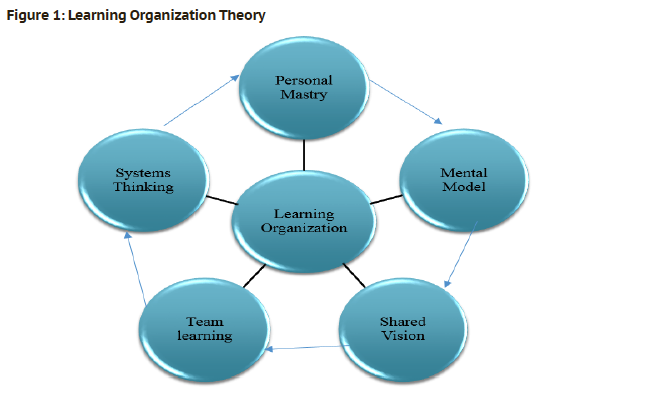

The learning organization theory was applied to this SR regarding implementing telemedicine during a pandemic much of the findings fit into the learning organization theory model. Senge in the late 1980s published the book “The Fifth Discipline: The art & practice of the learning organization” which redefined the organizational learning theory (Diane, 1995). According to Senge, employees in learning organizations expand their capacities to achieve desired results. Indeed, in the era of rapid change where all systems are interdependent, only flexible and adaptive organizations will excel and be productive.

The learning organization theory has five essential components, i.e.

Personal Mastery

Mental Model

Shared Vision

Team Learning

Systems Thinking

The theory is better explained when all of its components are understood and interpreted. Learning in any organization starts with the individual. Personal learning and mastery is the process in which changes in knowledge take place in individuals. As a follow on, organizational culture is the set of beliefs that are shared by the individuals of the organization (Heene & Sanchez, 1997).

The Mental Model is an explanation of an individual’s thoughts and interpretation of their surrounding world. So the individual must gain mastery that his/her perception about the knowledge is aligned with overall organizational objectives. Therefore, for knowledge has to be shared within the organization, it can be coded in terms of words, drawings symbols, or any other form, which is relevant for other members of the organization (Sanchez, 1997).

The learning process is directly linked with production. That means that the individual who is learning may come up with some influence to bring change. Learning takes place as a transformation process where information is transformed into knowledge (Jenson, 2005). A shared vision is essential to building a team because it promotes dialogue among the employees who have the same mental model. This provides the common cognitive foundation for productive discussion, which means the participants regard the information they shared and the information as unique for them (Nonaka, 1991). Once the team of individuals with the same vision brings up new idea, it is very challenging for them to communicate these ideas to the other groups and members of the organization. Management plays a vital role at this stage to make this knowledge sharing a regular process within an organization. This which collectively leads to systems thinking.

In short, as explained in Figure 1, all five components of the learning organization theory are critical, but the organization can only achieve the goals and desired output when the components work collectively.

Discussions

The learning organization concept is a continuous long term process which involves the cultural realignment of the organization. Before any healthcare provider becomes a learning organization, cultural change needs to start from the top, to ensure non-defensive behaviors (Argyris, 1991). This article discussed earlier that management plays an important role to implement any new change; it is vital that all stakeholders have a clear and shared vision.

To implement telemedicine, hospital management/ administration needs to learn many domains especially related to technology. However, every provider has their own technological needs depending on their services and workflows. Technological challenges related to implementing telemedicine are discussed in later sections. However, it is vital that healthcare teams need to be trained to effectively use this technology according to their specific workflows.

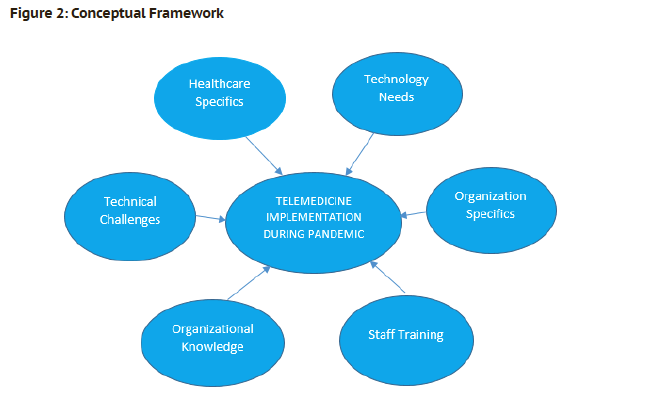

To effectively implement telemedicine, it is vital to assess the organization’s readiness and willingness to adopt the change. Every healthcare provider will have different and specific technological needs according to the levels of treatment and services provided. Similarly, organization knowledge and management’s commitment play an important role to provide the required resources, policies, and procedures that support the implementation of telemedicine.

In summary, as explained in figure 2, personal learning is a seed to achieve system thinking and organizations’ desired results. Gravin (1993) proposed that components of learning organization could be achieved in three phases:, cognitive, changed behavior, and output phase. In the healthcare provider scenario, the cognitive level is individual learning. In the second phase, the healthcare team is trained and equipped enough to meet the technological challenges; and in the third phase the organization will be on a right track to implement telemedicine with more confidence.

Research by Kyle Y. Faget (2020) found that the COVID-19 the telehealth landscape has shifted dramatically and will continue to shift as healthcare needs increase over time. During this pandemic, patients have not been comfortable visiting clinics, and healthcare professionals were challenged within the facilities to provide safe patient care. Telemedicine was introduced a long time but is not widely adopted by healthcare organizations. In the past, there have been a lot of challenges including government programs that might have been convenient for care and technology challenges but were an obstacle to providing virtual care.

In general, it is noticed that telehealth is very cost effective patient care, although patient visits, equipment used by the hospitals, labs/additional labs increase the cost and time of both the patient and the provider. If telehealth is in practice then office space, patient and provider’s travel time, additional labs, etc. will not be used so much as patients will have their technologies available and these can result in a lot of savings in the end. Telemedicine may be seen as an initial additional investment but over time this can save a lot of money.

Discussions

Telemedicine is becoming more relevant and impacting the way medicine is practiced. This is the future of addressing patient needs. Indeed, this Pandemic crisis presents unprecedented opportunities for making progress that should not be ignored. In this paper, we discussed available study materials and research materials outlining details and guidelines around telemedicine/telehealth. The researcher analyzed and synthesized emerging themes of the importance of telemedicine, technological challenges with telemedicine, and organizational readiness and training. During the COVID-19 pandemic, a significant increase has been noticed in the use of telemedicine. Government guidelines referenced in this research review talk about addressing the needs of telehealth. Technology has some challenges and interfacing with clinical applications still need some work.

The technology available today is capable of supporting all telemedicine needs and this use will be seen growing in the future. In today’s era of cloud computing and IT as a service model, this becomes very easy for hospitals to outsource the services they cannot manage well. Hospital organizations will need to bring cultural change, staff training, policies, investments, and willingness to change to get an advantage from telehealth. Patients are satisfied with the services of certain modalities in healthcare after initial hesitation of the change. Every hospital can customize their procedures and workflows depending upon their specialties and needs to facilitate and get the advantage of the technology overall and telemedicine in general.

Telemedicine surely saves time on the patient and the provider’s end. Technology has better reminders and accessibility and better time management for all of the stakeholders. We know that time is money and the value it bring in our lives by saving time is a very important and valuable factor to consider. Telemedicine provides a lot of flexibility in terms of scheduling, patient needs, accessibility, cost-effectiveness, and best service to patients and healthcare professionals. In conclusion, telemedicine is a rapidly growing market and more clinicians are becoming technology savvy. If healthcare providers follow the recommendations provided and become prepared as an organization to overcome the related challenges, they can easily and effectively implement telemedicine.

Discussions

The current study requires more detailed study and educational sessions/information dissemination sessions including all stakeholders on telemedicine. Future research should address the question of how to accurately measure patient satisfaction given this is a routinely used measure in health service. Similarly, future research may also improve the current evidence base by reporting on follow-up research, which investigates if patient and caregivers’ satisfaction with telehealth can be sustained over the long term. Some additional research is still required to find out more details for best practices for telemedicine.

References

Agee, J. (2009). Developing qualitative research questions: A reflective process. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 22(4), 431–447. https://doi.org/10.1080/09518390902736512

American Medical Association. (2020). COVID-19: AMA’s recent and ongoing advocacy efforts. Retrieved from American Medical Association website: https://www.ama-assn.org/delivering-care/public-health/covid-19-amas-recent-and-ongoing-advocacy-efforts

Argyris, C. (1991). Teaching smart people how to learn. Harvard Business Review, 69(3), 99–109.

Barney, A., Buckelew, S., Mesheriakova, V., & Raymond-Flesch, M. (2020). The COVID-19 pandemic and rapid implementation of adolescent and young adult telemedicine: Challenges and opportunities for innovation. Journal of Adolescent Health, 67(2). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2020.05.006

Bashshur, R., Doarn, C. R., Frenk, J. M., Kvedar, J. C., & Woolliscroft, J. O. (2020). Telemedicine and the COVID-19 pandemic, lessons for the future. Telemedicine and E-Health, 26(5). https://doi.org/10.1089/tmj.2020.29040.rb

Booth, A. (2006). Clear and present questions: Formulating questions for evidence based practice. Library Hi Tech, 24(3), 355–368. https://doi.org/10.1108/07378830610692127

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2020). Using Telehealth to Expand Access to Essential Health Services during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Retrieved from Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/telehealth.html

Day, J. A. (2020). Why Epic: Johns Hopkins Medicine. Retrieved from John Hopkins Medicine website: https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/epic/why_epic/

DeVay, Y. (2020). Navigating the expansion of telehealth and virtual services during the COVID-19 outbreak. Retrieved from Universy of Maryland Global Campus website: https://eds-a-ebscohost-com.ezproxy.umgc.edu/eds/pdfviewer/pdfviewer?vid=4&sid=f99e54a6-f105-4a5b-95d6-25003646b93f%40sessionmgr4006

Diane, W. (1995). The learning organization: Management theory for the information age or new age fad? Retrieved from The Journal of Academic Librarianship website: https://ac.els-cdn.com/0099133395900608/1-s2.0-0099133395900608-main.pdf

Edmunds, M., Tuckson, R., Lewis, J., Atchinson, B., Rheuban, K., Fanberg, H., … Thomas, L. (2017). An emergent research and policy framework for telehealth. EGEMs, 5(2), 1. https://doi.org/10.13063/2327-9214.1303

Eftekhar Ardebili, M., Naserbakht, M., Bernstein, C., Alazmani-Noodeh, F., Hakimi, H., & Ranjbar, H. (2020). Healthcare providers experience of working during the COVID-19 pandemic: A qualitative study. American Journal of Infection Control, 49(5). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajic.2020.10.001

Faget, K. Y. (2020). Telehealth in the wake of COVID-19. Retrieved from University of Maryland Global Campus website: https://eds-a-ebscohost-com.ezproxy.umgc.edu/eds/pdfviewer/pdfviewer?vid=7&sid=f99e54a6-f105-4a5b-95d6-25003646b93f%40sessionmgr4006

Garvin, D. (1993). Building a learning organization. Retrieved from Harvard Business Review website: https://hbr.org/1993/07/building-a-learning-organization

George, G., Ferguson, L. A., & Pearce, P. (2014). Finding a needle in the haystack: Performing an in-depth literature search to answer a clinical question. Nursing: Research and Reviews, 4, 65–76. https://doi.org/10.2147/nrr.s63578

Gough, D., Oliver, S., & Thomas, J. (2012). Systematic reviews and research. Los Angeles: Sage Reference.

Harvey, M. J., & Harvey, M. G. (2014). Privacy and security issues for mobile health platforms. Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology, 65(7), 1305–1318. https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.23066

Jensen, P. E. (2005). A contextual theory of learning and the learning organization. Knowledge and Process Management, 12(1), 53–64. https://doi.org/10.1002/kpm.217

Kreidler, M. L. (2022). Health care and information technology. Retrieved January 5, 2022, from Salem Press Encyclopedia website: https://eds-a-ebscohost-com.ezproxy.umgc.edu/eds/detail/detail?vid=2&sid=d5f57170-cb89-416d-8592-026f6830b1d8%40sdc-v-sessmgr02&bdata=JnNpdGU9ZWRzLWxpdmUmc2NvcGU9c2l0ZQ%3d%3d#AN=89163746&db=ers

Levingston, S. A. (2013). Electronic health records’ “make-or-break year.” Retrieved from Bloomberg Businessweek website: http://www.businessweek.com/articles/2013-11-14/2014-outlook-electronic-health-records-make-or-break-year

Li, H. K. (1999). Telemedicine and ophthalmology. Survey of Ophthalmology, 44(1), 61–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0039-6257(99)00059-4

Link, M. M. (1965). Space Medicine in Project Mercury. NASA SP-4003. Retrieved from Harvard Article Database website: http://articles.adsabs.harvard.edu/full/1965NASSP4003…..L

Medicare and Medicade Programs. (2020). Policy and regulatory revisions in response to the COVID-19 public health emergency. In Federal Register (pp. 1–63). Retrieved from Department of Health and Human Services website: https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-2020-04-06/pdf/2020-06990.pdf

National Consortium of Telehealth Resource Centers. (n.d.). Retrieved from National Consortium of Telehealth Research Centers website: https://www.telehealthresourcecenter.org/

Nonaka, I. (1991). The knowledge-creating company. Harvard Business Review, 96–104. Retrieved from https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/da2f/d9e368f14e0bb713fb6f4d7c32b0f72f6bcf.pdf

Orlando, J. F., Beard, M., & Kumar, S. (2019). Systematic review of patient and caregivers’ satisfaction with telehealth videoconferencing as a mode of service delivery in managing patients’ health. PLOS ONE, 14(8), e0221848. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0221848

Parks, R., Wigand, R. T., Othmani, M. B., Serhier, Z., & Bouhaddou, O. (2019). Electronic health records implementation in Morocco: Challenges of silo efforts and recommendations for improvements. International Journal of Medical Informatics, 129, 430–437. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2019.05.026

Pollock, K., Setzen, M., & Svider, P. F. (2020). Embracing telemedicine into your otolaryngology practice amid the COVID-19 crisis: An invited commentary. American Journal of Otolaryngology, 41(3), 102490. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjoto.2020.102490

Prager, E. M., Chambers, K. E., Plotkin, J. L., McArthur, D. L., Bandrowski, A. E., Bansal, N., … Graf, C. (2018). Improving transparency and scientific rigor in academic publishing. Journal of Neuroscience Research, 97(4), 377–390. https://doi.org/10.1002/jnr.24340

Rimsza, M. E., Hotaling, A. J., Keown, M. E., Marcin, J. P., Moskowitz, W. B., Sigrest, T. D., & Simon, H. K. (2015). The Use of Telemedicine to Address Access and Physician Workforce Shortages. Pediatrics, 136(1), 202–209. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2015-1253

Sanchez, R. (1997). Managing articulated knowledge in competence-based competition. In In Strategic Learning and Knowledge Managemen (pp. 163–187). Chichester: Wiley.

Sanchez, R., & Aimé Heene. (1997). Strategic learning and knowledge management. Chichester: Wiley.

Smith, W. R., Atala, A. J., Terlecki, R. P., Kelly, E. E., & Matthews, C. A. (2020). Implementation guide for rapid integration of an outpatient telemedicine program during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of the American College of Surgeons, 231(2). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2020.04.030

Telehealth. (n.d.). HHS.gov: How to get or provide remote health care. Retrieved from telehealth.hhs.gov website: https://www.telehealth.hhs.gov/

Telehealth. (n.d.). Retrieved from American Association of Nurse Practitioners website: https://www.aanp.org/advocacy/advocacy-resource/position-statements/telehealth

UMGC. (n.d.-a). First Cycle Coding. Retrieved from University of Maryland Global Campus website: https://lti.umuc.edu/contentadaptor/page/topic?keyword=First%20Cycle%20Coding

UMGC. (n.d.-b). QDA: Deductive versus inductive coding. Retrieved from University of Maryland Global Campus website: https://lti.umuc.edu/contentadaptor/topics/byid/9f0de276-d936-4414-9bb8-318ef584bc28

UMGC. (n.d.-c). Thematic Synthesis. Retrieved from University of Maryland Global Campus website: https://lti.umuc.edu/contentadaptor/page/topic?keyword=Thematic%20Synthesis